Science Snapshots: Hurricane Hunters

Jerald has waited long enough, so it's time to talk about Hurricane Hunters!

|

| Courtesy NOAA |

Note I'll be talking about US-based planes and organizations only, as that is what I'm familiar with. If you know about the equivalent activities from your home country, please feel free to share details in the comments!

Hurricane Hunters are essentially airborne storm chasers who fly into hurricanes/typhoons/tropical cyclones. Except they are sanctioned by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), rather than just any random in a plane who feels like they can fly into a storm (looking at you, non-meteorologist storm chasers who risk the lives of everyone around you). While my understanding is that it's the experience of a lifetime based on people I know who have gone, the goal at the end of the day is to improve hurricane forecasts to better protect life and property. In addition to NOAA's crew, the US Air Force's 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron also flies into these storms. You can read more about the specific aircraft at these two links because I know very little about aircraft. I do know NOAA uses P-3's a lot. Whatever that means. My organization has C-130s. We fly into land-based crap. I do not and will not ever be on one of those flights, because I have the motion sickness and every flight would be very unfun for my colleagues, not to mention me.

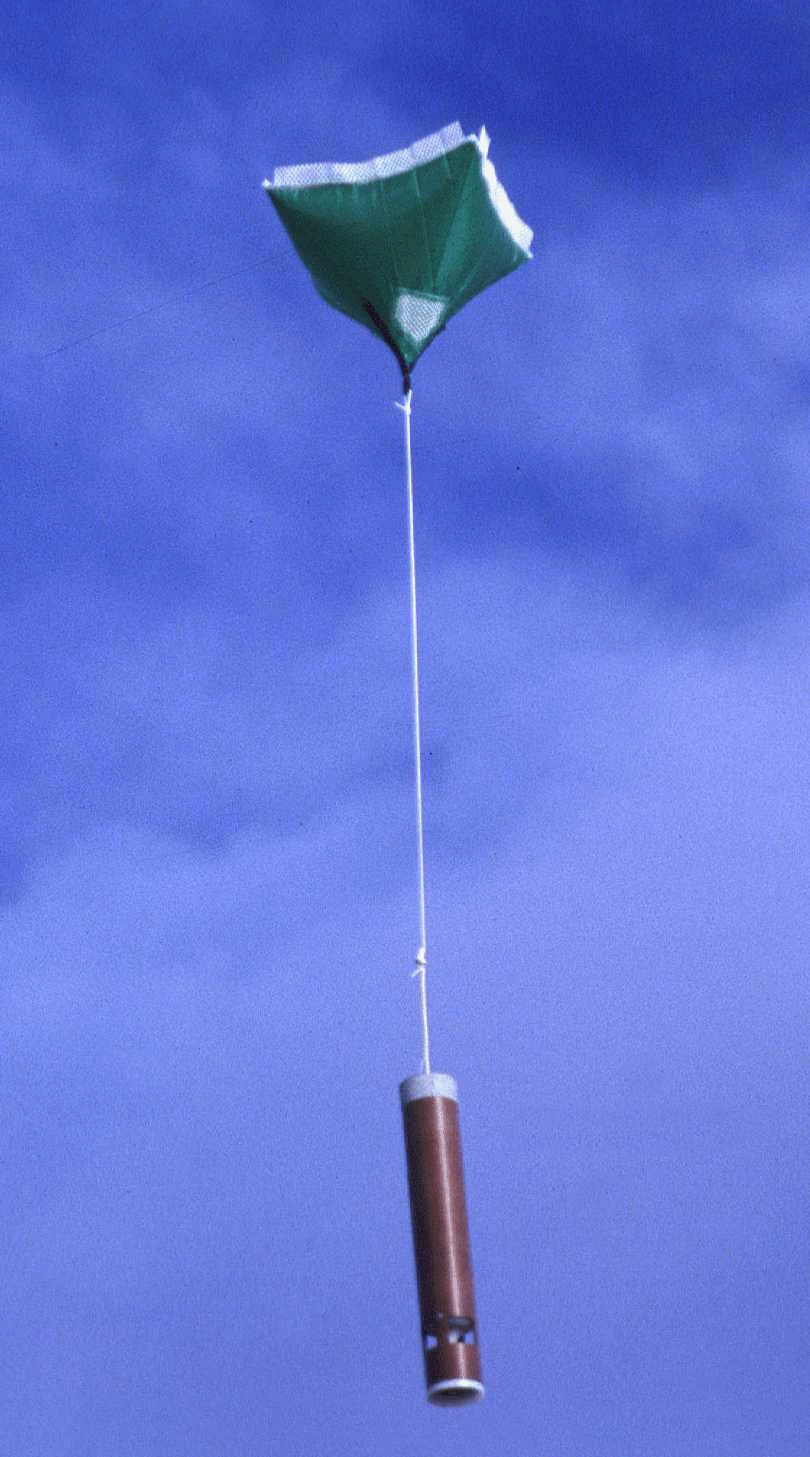

The planes used are heavily instrumented and are essentially flying weather stations. In addition to Doppler radar and any on-board probes, the crews also release dropsondes into the storm. These are like backwards weather balloons: instead of taking off at the surface and transmitting data as they rise, dropsondes transmit data as they fall to the surface. Air temperature, humidity, air pressure, wind direction and speed, and sometimes sea surface temperature are all returned to the National Hurricane Center. This supplements fixed surface stations, like buoys, and satellite imagery for the forecasters determining how strong the storm is and how it is changing through time. This, in turn, helps them give a better forecast. We can also stick these data into the weather models to improve the predictions they provide, as well as verify how well they have been doing.

|

| A dropsonde, via NCAR's Earth Observing Laboratory |

Hurricanes happen where the instruments just don't exist. There are no weather balloons launched off the ocean. In the image below, the red dots represent the radiosonde (weather balloon) locations in the Gulf of Mexico region. Ignore any non-red dots.

|

| From Douglas (2023) |

|

| Screenshot from National Data Buoy Center |

Since hurricanes happen over the ocean until they're mowing us down, it's really difficult to get observations from our current network. That's where the Hurricane Hunters come in.

|

| Source: Denton Record-Chronicle |

Comments

Post a Comment